This investigation was published in partnership with The Marshall Project and FRONTLINE (PBS).

When the DNA results came back, even Lukis Anderson thought he might have committed the murder.

“I drink a lot,” he remembers telling public defender Kelley Kulick as they sat in a plain interview room at the Santa Clara County, California, jail. Sometimes he blacked out, so it was possible he did something he didn’t remember. “Maybe I did do it.”

Kulick shushed him. If she was going to keep her new client off death row, he couldn’t go around saying things like that. But she agreed. It looked bad.

Before he was charged with murder, Anderson was a 26-year-old homeless alcoholic with a long rap sheet who spent his days hustling for change in downtown San Jose. The murder victim, Raveesh Kumra, was a 66-year-old investor who lived in Monte Sereno, a Silicon Valley enclave 10 miles and many socioeconomic rungs away.

Around midnight on November 29, 2012, a group of men had broken into Kumra’s 7,000-square-foot mansion. They found him watching CNN in the living room, tied him, blindfolded him, and gagged him with mustache-print duct tape. They found his companion, Harinder, asleep in an upstairs bedroom, hit her on the mouth, and tied her up next to Raveesh. Then they plundered the house for cash and jewelry.

After the men left, Harinder, still blindfolded, felt her way to a kitchen phone and called 911. Police arrived, then an ambulance. One of the paramedics declared Raveesh dead. The coroner would later conclude that he had been suffocated by the mustache tape.

Three and a half weeks later, the police arrested Anderson. His DNA had been found on Raveesh’s fingernails. They believed the men struggled as Anderson tied up his victim. They charged him with murder. Kulick was appointed to his case.

Public defender Kelley Kulick was appointed to Lukis Anderson’s case after he was charged with first-degree murder. CARLOS CHAVARRÍA/THE MARSHALL PROJECT

As they looked at the DNA results, Anderson tried to make sense of a crime he had no memory of committing.

“Nah, nah, nah. I don’t do things like that,” he recalls telling her. “But maybe I did.”

“Lukis, shut up,” Kulick says she told him. “Let’s just hit the pause button till we work through the evidence to really see what happened.”

What happened, although months would pass before anyone figured it out, was that Lukis Anderson’s DNA had found its way onto the fingernails of a dead man he had never even met.

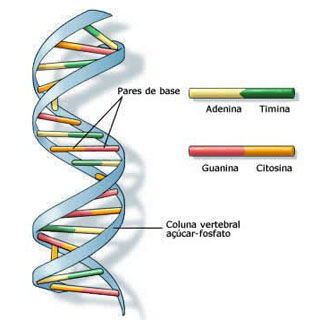

BACK IN THE 1980s, when DNA forensic analysis was still in its infancy, crime labs needed a speck of bodily fluid—usually blood, semen, or spit—to generate a genetic profile.

That changed in 1997, when Australian forensic scientist Roland van Oorschot stunned the criminal justice world with a nine-paragraph paper titled “DNA Fingerprints from Fingerprints.” It revealed that DNA could be detected not just from bodily fluids but from traces left by a touch. Investigators across the globe began scouring crime scenes for anything—a doorknob, a countertop, a knife handle—that a perpetrator may have tainted with incriminating “touch” DNA.

Everyone, including Anderson, leaves a trail of DNA everywhere they go. CARLOS CHAVARRÍA/THE MARSHALL PROJECT

Sometimes that DNA can end up at a crime scene. CARLOS CHAVARRÍA/THE MARSHALL PROJECT

But van Oorschot’s paper also contained a vital observation: Some people’s DNA appeared on things that they had never touched.

In the years since, van Oorschot’s lab has been one of the few to investigate this phenomenon, dubbed “secondary transfer.” What they have learned is that, once it’s out in the world, DNA doesn’t always stay put.

In one of his lab’s experiments, for instance, volunteers sat at a table and shared a jug of juice. After 20 minutes of chatting and sipping, swabs were deployed on their hands, the chairs, the table, the jug, and the juice glasses, then tested for genetic material. Although the volunteers never touched each other, 50 percent wound up with another’s DNA on their hand. A third of the glasses bore the DNA of volunteers who did not touch or drink from them.

Then there was the foreign DNA—profiles that didn’t match any of the juice drinkers. It turned up on about half of the chairs and glasses, and all over the participants’ hands and the table. The only explanation: The participants unwittingly brought with them alien genes, perhaps from the lover they kissed that morning, the stranger with whom they had shared a bus grip, or the barista who handed them an afternoon latte.

In a sense, this isn’t surprising: We leave a trail of ourselves everywhere we go. An average person may shed upward of 50 million skin cells a day. Attorney Erin Murphy, author of Inside the Cell, a book about forensic DNA, has calculated that in two minutes the average person sheds enough skin cells to cover a football field. We also spew saliva, which is packed with DNA. If we stand still and talk for 30 seconds, our DNA may be found more than a yard away. With a forceful sneeze, it might land on a nearby wall.

To find out the prevalence of DNA in the world, a group of Dutch researchers tested 105 public items—escalator rails, public toilet door handles, shopping basket handles, coins. Ninety-one percent bore human DNA, sometimes from half a dozen people. Even items intimate to us—the armpits of our shirts, say—can bear other people’s DNA, they found.

The itinerant nature of DNA has serious implications for forensic investigations. After all, if traces of our DNA can make their way to a crime scene we never visited, aren’t we all possible suspects?

Forensic DNA has other flaws: Complex mixtures of many DNA profiles can be wrongly interpreted, certainty statistics are often wildly miscalculated, and DNA analysis robots have sometimes been stretched past the limits of their sensitivity.

But as advances in technology are solving some of these problems, they have actually made the problem of DNA transfer worse. Each new generation of forensic tools is more sensitive; labs today can identify people with DNA from just a handful of cells. A handful of cells can easily migrate.

A survey of the published science, interviews with leading scientists, and a review of thousands of pages of court and police documents associated with the Kumra case has elucidated how secondary DNA transfer can undermine the credibility of the criminal justice system’s most-trusted tool. And yet, very few crime labs worldwide regularly and robustly study secondary DNA transfer.

This is partly because most forensic scientists believe DNA to be the least of their field’s problems. They’re not wrong: DNA is the most accurate forensic science we have. It has exonerated scores of people convicted based on more flawed disciplines like hair or bite-mark analysis. And there have been few publicized cases of DNA mistakenly implicating someone in a crime.

But, like most human enterprises, DNA analysis is not perfect. And without study, the scope and impact of that imperfection is difficult to assess, says Peter Gill, a British forensic researcher. He has little doubt that his field, so often credited with solving crimes, is also responsible for wrongful convictions.

“The problem is we’re not looking for these things,” Gill says. “For every miscarriage of justice that is detected, there must be a dozen that are never discovered.”

THE PHONE RANG five times.

“Are you awake?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yeah,” lied Corporal Erin Lunsford.

“Are you back on full duty or you still light duty?” she asked, according to a tape of the call.

Lunsford had been off crutches for two weeks already, but it was 2:15 am and pouring rain. Probably some downed tree needed to be policed. “Light duty,” Lunsford said.

“Oh,” she said. “Never mind.”

“Why, what are you calling about?” he asked.

“We had a home invasion that turned into a 187,” she said. Cop slang for murder.

“Shit, seriously?” Lunsford said, waking up.

Sergeant Erin Lunsford of the Los Gatos-Monte Sereno Police Department was the lead investigator in Kumra’s murder. CARLOS CHAVARRÍA/THE MARSHALL PROJECT

Lunsford had served all 15 of his professional years as a police officer at the Los Gatos–Monte Sereno Police Department, a 38-officer agency that policed two drowsy towns. He rose through the ranks and was working a stint in the department’s detective bureau. He had mostly been investigating property crimes. Los Gatos, a wealthy bedroom community of Silicon Valley, averaged a homicide once every three or four years. Monte Sereno, a bedroom community of the bedroom community, hadn’t had a homicide in roughly 20.

Lunsford got dressed. He drove through the November torrent. He spotted cop cars clustered around a brick and iron gate. An ambulance flashed quietly in the driveway. Beyond it, the lit Kumra mansion.

Lunsford’s boss told him to take the lead on the investigation. The on-scene supervisor walked him through the house. Dressers emptied, files dumped. A cellphone in a toilet, pissed on. A refrigerator beeping every 10 seconds, announcing its doors were ajar. Raveesh’s body, heavyset and disheveled, on the floor near the kitchen. His eyes still blindfolded.

An investigator from the county coroner’s office arrived and moved Kumra’s body into a van. Lunsford followed her to the morgue for the autopsy. A doctor undressed the victim and scraped and cut his fingernails for evidence.

Lunsford recognized Raveesh, a wealthy businessman who had once owned a share of a local concert venue. Lunsford had come to the Kumra mansion a couple times on “family calls” that never amounted to anything: “Just people arguing,” he recalled. He had also run into him at Goguen’s Last Call, a dive frequented by Raveesh as a regular and Lunsford as a cop responding to calls. Raveesh was an affable extrovert, always buying rounds; the unofficial mayor of that part of town, Lunsford called him.

In the coming days, as Lunsford interviewed people who knew the Kumras, he was told that Raveesh also had relationships with sex workers. Raveesh and Harinder had divorced around 2010 after more than 30 years of marriage, but still lived together.

While Lunsford attended the autopsy, a team of gloved investigators combed the mansion. They tucked paper evidence into manila envelopes; bulkier items into brown paper bags. They amassed more than 100.

Teams specializing in crime scene investigations were first assembled over a century ago, after the French scientist Edmond Locard devised the principle that birthed the field of forensics: A perpetrator will bring something to a crime scene and leave with something from it. Van Oorschot’s touch DNA discovery had unveiled the most literal expression imaginable of Locard’s principle.

Like those early teams, the investigators in the Kumra mansion were looking for fingerprints, footprints, and hair. But unlike their predecessors, they devoted considerable time to thinking through everything the perpetrators may have touched.

Some perpetrators are giving thought to this as well. A 2013 Canadian study of 350 sexual homicides found that about a third of perpetrators appeared to have taken care not to leave DNA, killing their victims in tidier ways than beating or strangling, which are likely to leave behind genetic clues, for instance. And it worked: In those “forensically aware” cases, police solved the case 50 percent of the time, compared to 83 percent of their sloppier counterparts.

The men who killed Kumra seemed somewhat forensically aware, albeit clumsily. They had worn latex gloves through their rampage; a pile of them were left in the kitchen sink, wet and soapy, as though someone had tried to wash off the DNA.

In the weeks after the murder, Tahnee Nelson Mehmet, a criminalist at the county crime lab, ran dozens of tests on the evidence collected from the Kumra mansion. Most only revealed DNA profiles consistent with Raveesh or Harinder.

But in her first few batches of evidence, Mehmet hit forensic pay dirt: a handful of unknown profiles—including on the washed gloves. She ran them through the state database of people arrested for or convicted of felonies and got three hits, all from the Bay Area: 22-year-old DeAngelo Austin on the duct tape; 21-year-old Javier Garcia on the gloves; and, on the fingernail clippings, 26-year-old Lukis Anderson.

WITHIN WEEKS OF the DNA hits, Lunsford had plenty of evidence implicating Austin and Garcia: Both were from Oakland, but a warrant for their cellphone records showed they’d pinged towers near Monte Sereno the night of the homicide. Police records showed that Austin belonged to a gang linked to a series of home burglaries. And most damning of all, Austin’s older sister, a 32-year-old sex worker named Katrina Fritz, had been involved with Raveesh for 12 years. Police had even found her phone backed up on Raveesh’s computer. Eventually she would admit that she had given her brother a map of the house.

Connecting Anderson to the crime proved trickier. There were no phone records showing he had traveled to Monte Sereno that night. He wasn’t associated with a gang. But one thing on his rap sheet drew Lunsford’s attention: A felony residential burglary.

Eventually Lunsford found a link. A year earlier, Anderson had been locked up in the same jail as a friend of Austin’s named Shawn Hampton. Hampton wore an ankle monitor as a condition of his parole. It showed that two days before the crime he had driven to San Jose. He made a couple of stops downtown, right near Anderson’s territory.

It started to crystallize for Lunsford: When Austin was planning the break-in, he wanted a local guy experienced in burglary. So Hampton hooked him up with his jail buddy Anderson.

Anderson had recently landed back in jail after violating his probation on the burglary charge. Lunsford and his boss, Sergeant Mike D’Antonio, visited him there. They taped the interview.

“Does this guy look familiar to you? What about this lady?” Lunsford said, laying out pictures of the victims on the interview room table.

“I don’t know, man,” Anderson said.

Lunsford pulled out a picture of Anderson’s mother.

“All right, what about this lady here? You don’t know who she is?” Lunsford said.

Anderson met Lunsford’s sarcasm with silence.

Lunsford set down a letter from the state of California showing the database match between Anderson’s DNA and the profile found on the victim’s fingernails.

“This starting to ring some bells?” Lunsford said.

“My guess is you didn’t think anybody was gonna be home,” D’Antonio said. “My guess is it went way farther than you ever thought it would go.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, sir,” Anderson said.

“You do,” Lunsford said. “You won’t look at their pictures. The only picture you looked at good was your mom.”

Finally, D’Antonio took a compromising tone.

“Lukis, Lukis, Lukis,” he said. “I don’t have a crystal ball to know what the truth is. Only you do. And in all the years I’ve been doing this I’ve never seen a DNA hit being wrong.”

ANDERSON HAD BEEN in jail on the murder charge for over a month when a defense investigator dropped a stack of records on Kulick’s desk. Look at them, the investigator said. Now.

They were Anderson’s medical records. Because his murder charge could carry the death penalty, Kulick had the investigator pull everything pertinent to Anderson’s medical history, including his mental health, in case they had to ask for leniency during sentencing.

She suspected Anderson could be a good candidate for such leniency. He spent much of his childhood homeless. In early adulthood, he was diagnosed with a mental health disorder and diabetes. And he had developed a mighty alcohol addiction. One day, while drunk, he stepped off a curb and into the path of a moving truck. He survived, but his memory was never quite right again. He lost track of days, sometimes several in a row.

That’s not to say his life was bleak. He made friends easily. He had a coy sense of humor and dimples that shone like headlights. His buddies, many on the streets themselves, looked after him, as did some downtown shopkeepers. Kulick and her investigator had spoken to several of them. They shook their heads. Anderson might be a drunk, they said, but he wasn’t a killer.

His rap sheet seemed to agree. It was filled with petty crimes: drunk in public, riding a bike under the influence, probation violations. The one serious conviction—the residential burglary that had caught Lunsford’s attention—seemed more benign upon careful reading. According to the police report, Anderson had drunkenly broken the front window of a home and tried to crawl through. The horrified resident had pushed him back out with blankets. Police found him a few minutes later standing on the sidewalk, dazed and bleeding. Though nothing had been stolen, he had been charged with a felony and pleaded no contest. His DNA was added to the state criminal database.

The medical records showed that Anderson was also a regular in county hospitals. Most recently, he had arrived in an ambulance to Valley Medical Center, where he was declared inebriated nearly to the point of unconsciousness. Blood alcohol tests indicated he had consumed the equivalent of 21 beers. He spent the night detoxing. The next morning he was discharged, somewhat more sober.

The date on that record was November 29. If the record was right, Anderson had been in the hospital precisely as Raveesh Kumra was suffocating on duct tape miles away.

Kulick remembers turning to the investigator, who was staring back at her. She was used to alibis being partial and difficult to prove. This one was signed by hospital staff. More than anything, she felt terrified. “To know that you have a factually innocent client sitting in jail facing the death penalty is really scary,” she said later. “You don’t want to screw up.”

She knew Lunsford and the prosecutors would try to find holes: Perhaps the date on the record was wrong, or someone had stolen his ID, or there was more than one Lukis Anderson.

So she and the investigator systematically retraced his day. Anderson had only patchy recollections of the night in question. But they found a record that a 7-Eleven clerk called authorities at 7:54 pm complaining that Anderson was panhandling. He moved on before the police arrived.

His meanderings took him four blocks east, to S&S Market. The clerk there told Kulick that Anderson sat down in front of the store at about 8:15 pm, already drunk, and got drunker. A couple of hours later, he wandered into the store and collapsed in an aisle. The clerk called the authorities.

The police arrived first, followed by a truck from the San Jose Fire Department. A paramedic with the fire department told Kulick he had picked up Anderson drunk so often that he knew his birth date by heart. Two other paramedics arrived with an ambulance. They wrestled Anderson onto a stretcher and took him to the hospital. According to his medical records, he was admitted at 10:45 pm. The doctor who treated him said Anderson remained in bed through the night.

Harinder Kumra had said the men who killed Raveesh rampaged through her house sometime between 11:30 pm and 1:30 am.

Kulick called the district attorney’s office. She wanted to meet with them and Lunsford.

IN 2008, GERMAN detectives were on the trail of the “Phantom of Heilbronn.” A serial killer and thief, the Phantom murdered immigrants and a cop, robbed a gemstone trader, and munched on a cookie while burglarizing a caravan. Police mobilized across borders, offered a large reward, and racked up more than 16,000 hours on the hunt. But they struggled to discern a pattern to the crimes, other than the DNA profile the Phantom left at 40 crime scenes in Germany, France, and Austria.

At long last, they found the Phantom: An elderly Polish worker in a factory that produced the swabs police used to collect DNA. She had somehow contaminated the swabs as she worked. Crime scene investigators had, in turn, contaminated dozens of crime scenes with her DNA.

Contamination, the unintentional introduction of DNA into evidence by the very people investigating the crime, is the best understood form of transfer. And after Lunsford heard Kulick’s presentation—then retraced Anderson’s day himself, concluded he had jailed an innocent man, and felt sick to his stomach for a while—he counted contamination among his leading theories.

As the Phantom of Heilbronn case demonstrated, contamination can happen long before evidence arrives in a lab. A 2016 study by Gill, the British forensic researcher, found DNA on three-quarters of crime scene tools he tested, including cameras, measuring tapes, and gloves. Those items can pick up DNA at one scene and move it to the next.

Once it arrives in the lab, the risk continues: One set of researchers found stray DNA in even the cleanest parts of their lab. Worried that the very case files they worked on could be a source of contamination, they tested 20. Seventy-five percent held the DNA of people who hadn’t handled the file.

In Santa Clara County, the district attorney’s office reviewed the Kumra case and found no obvious evidence of errors or improper use of tools in the crime lab. They checked if Anderson’s DNA had shown up in any other cases the lab had recently handled, and inadvertently wandered into the Kumra case. It had not.

So they began investigating a second theory: That Raveesh and Anderson somehow met in the hours or days before the homicide, at which point Anderson’s DNA became caught under Raveesh’s fingernails.

“We are convinced that at some point—we just don’t know when in the 24 hours, 48 hours, or 72 hours beforehand—that their paths crossed,” deputy district attorney Kevin Smith told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter.

THERE NOW EXISTS a small pile of studies exploring how DNA moves: If a man shakes someone’s hand and then uses the restroom, could their DNA wind up on his penis? (Yes.) If someone drags another person by the ankles, how often does their profile clearly show up? (40 percent of the time.) And, of utmost relevance to Lukis Anderson, how many of us walk around with traces of other people’s DNA on our fingernails? (1 in 5.)

Whether someone’s DNA moves from one place to another—and then is found there—depends on a handful of factors: quantity (two transferred cells are less likely to be detected than 2,000), vigor of contact (a limp handshake relays less DNA than a bone-crushing one), the nature of the surfaces involved (a tabletop’s chemical content affects how much DNA it picks up), and elapsed time (we’re more likely carrying DNA of someone we just hugged than someone we hugged hours ago, since foreign DNA tends to rub off over time).

Then there’s a person’s shedding status: “Good” shedders lavish their DNA on their environment; “poor” shedders move through the world virtually undetectable, genetically speaking. In general, flaky, sweaty, or diseased skin is thought to shed more DNA than healthy, arid skin. Nail chewers, nose pickers, and habitual face touchers spread their DNA around, as do hands that haven’t seen a bar of soap lately—discarded DNA can accumulate over time, and soap helps wash it away.

And some people simply seem to be naturally superior shedders. Mariya Goray, a forensic science researcher in van Oorschot’s lab who coauthored the juice study with him, has found one of her colleagues to be an outrageously prodigious shedder. “He’s amazing,” she said, her voice tinged with admiration. “Maybe I’ll do a study on him. And the study will just be called, ‘James.'”

She hopes to develop a test to determine a person’s shedder status, which could be deployed to assess a suspect’s claims that their DNA arrived somewhere innocently.

Such a test could have been useful in the case of David Butler, an English cabdriver. In 2011, DNA found on the fingernails of a woman who had been murdered six years earlier was run through a database and matched Butler’s. He swore he’d never met the woman. His defense attorney noted that he had a skin condition so severe that fellow cabbies had dubbed him “Flaky.” Perhaps he had given a ride to the actual murderer that day, who inadvertently picked up Butler’s DNA in the cab and later deposited it on the victim, they theorized.

Investigators didn’t buy the explanation, but jurors did. Butler was acquitted after eight months in jail. Upon release, he excoriated police for their blind faith in the evidence.

“DNA has become the magic bullet for the police,” Butler told the BBC. “They thought it was my DNA, ergo it must be me.”

TRADITIONAL POLICE WORK would have never steered police to Anderson. But the DNA hit led them to seek other evidence confirming his guilt. “It wasn’t malicious. It was confirmation bias,” Kulick says. “They got the DNA, and then they made up a story to fit it.”

Had the case gone to trial, jurors may well have done the same. A 2008 series of studies by researchers at the University of Nevada, Yale, and Claremont McKenna College found that jurors rated DNA evidence as 95 percent accurate and 94 percent persuasive of a suspect’s guilt.

Eleven leading DNA transfer scientists contacted for this story were in consensus that the criminal justice system must be willing to question DNA evidence. They were also in agreement about whose job it should be to navigate those queries: forensic scientists.

As it stands, forensic scientists generally stick to the question of source (whose DNA is this?) and leave activity (how did it get here?) for judges and juries to wrestle with. But the researchers contend that forensic scientists are best armed with the information necessary to answer that question.

Consider a case in which a man is accused of sexually assaulting his stepdaughter. He looks mighty guilty when his DNA and a fragment of sperm is found on her underwear. But jurors might give the defense more credence if a forensic scientist familiarized them with a 2016 Canadian study showing that fathers’ DNA is frequently found on their daughters’ clean underwear; occasionally, a fragment of sperm is there too. It migrates there in the wash.

This shift—from reporting on who to reporting on how—has been encouraged by the European Network of Forensic Science Institutes. But the shift has been slow on that continent and virtually nonexistent in the United States, where defense attorneys have argued that forensic scientists—in many communities employed by the prosecutor’s office or police department—should be careful to stick to the facts rather than make conjectures.

“The problem is that when forensic scientists get involved in those determinations, they’re wrought with confirmation bias,” says Jennifer Friedman, a Los Angeles County public defender.

Meanwhile, forensic scientists in the US have resisted the shift, arguing they lack the data to confidently testify about how DNA moves.

Van Oorschot and Gill concede this point. Only a handful of labs in Europe and Australia regularly research transfer. The forensic scientists interviewed for this story say they are not aware of any lab or university in the US that routinely does so.

Funding gets some of the blame: The Australian labs and some European labs get government dollars to study DNA transfer. But British forensic researcher and professor Georgina Meakin of University College London says she must find alternative ways to pay for her own transfer research; the Centre for Forensic Sciences, where Meakin works, has launched a crowdfunding page for a new lab to study trace evidence transfer. In the US, all the grants from the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Science and Technology, and the National Institute of Justice for forensics research put together likely sum just $13.5 million a year, according to a 2016 report on forensic science by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST); of that, very little has been spent looking into DNA transfer.

“The folks with the greatest interest in making sure forensic science isn’t misused are defendants,” says Eric Lander, principal leader of the Human Genome Project, who cochaired PCAST under President Obama. “Defendants don’t have an awful lot of power.”

In 2009, after issuing a report harshly criticizing the paucity of science behind most forensics, the National Academy of Sciences urged Congress to create a new, independent federal agency to oversee the field. There was little political appetite to do that. Instead, in 2013, Obama created a 40-member National Commission on Forensic Science, filled it with people who saw forensics from radically different perspectives—prosecutors, defense attorneys, academics, lab analysts, and scientists—and made a rule that all actions must be approved by a supermajority. Naturally, the commission got off to a slow start. But ultimately it produced more than 40 recommendations and opinions. These lacked the teeth of a regulatory ruling, but the Justice Department was obligated to respond to them.

At the beginning, most of the commission’s efforts were focused on improving other disciplines, “because DNA testing as a whole is so much better than much forensic science that we had focused a lot of our attention elsewhere,” says US district judge Jed Rakoff, a member of the commission.

According to Rakoff and other members interviewed, the commission was just digging into issues touching on DNA transfer when attorney general Jeff Sessions took office last year. In April 2017, his department announced it would not renew the commission’s charter. It never met again.

Then, in August, President Trump signed the Rapid DNA Act of 2017, allowing law enforcement to use new technology that produces DNA results in just 90 minutes. The bill had bipartisan support and received little press. But privacy advocates worry it may usher in an era of widespread “stop and spit” policing, in which law enforcement asks anyone they stop for a DNA sample. This is already occurring in towns in Florida, Connecticut, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, according to reporting by ProPublica. If law enforcement deems there is probable cause, they can compel someone to provide DNA; otherwise, it is voluntary.

If stop-and-spit becomes more widely used and police databases swell, it could have a disproportionate impact on African Americans and Latinos, who are more often searched, ticketed, and arrested by police. In most states, a felony arrest is enough to add someone in perpetuity to the state database. Just this month, the California Supreme Court declined to overturn a provision requiring all people arrested or charged for a felony to give up their DNA; in Oklahoma, the DNA of any undocumented immigrant arrested on suspicion of any crime is added to a database. Those whose DNA appears in a database face a greater risk of being implicated in a crime they didn’t commit.

IT WAS LUNSFORD who figured it out in the end.

He was reading through Anderson’s medical records and paused on the names of the ambulance paramedics who picked up Anderson from his repose on the sidewalk outside S&S Market. He had seen them before.

He pulled up the Kumra case files. Sure enough, there were the names again: Three hours after picking up Anderson, the two paramedics had responded to the Kumra mansion, where they checked Raveesh’s vitals.

The prosecutors, defense attorney, and police agree that somehow, the paramedics must have moved Anderson’s DNA from San Jose to Monte Sereno. Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen has postulated that a pulse oximeter slipped over both patients’ fingers may have been the culprit; Kulick thinks it could have been their uniforms or another piece of equipment. It may never be known for sure.

A spokesman for Rural/Metro Corporation, where the paramedics worked, told San Francisco TV station KPIX5 that the company had high sanitation standards, requiring paramedics to change gloves and sanitize the vehicles.

Deputy District Attorney Smith framed the incident as a freak accident. “It’s a small world,” he told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter.

The trial against the other men implicated in the case moved forward. Austin’s older sister, Fritz, testified in trials against him and Garcia. She also testified against a third man, Marcellous Drummer, whose DNA had been found on evidence from the Kumra crime scene months after the initial hits.

During the trials, Harinder Kumra told jurors she was still haunted by the image of the man who split her lip open. “Every day I see that face. Every night when I sleep, when there’s a noise, I think it’s him,” she said. She has sold the mansion. Members of the Kumra family declined to comment for this story.

The DNA in the case did not go uncontested. Garcia’s attorney argued that, like Anderson’s, Garcia’s DNA had arrived at the scene inadvertently. According to the attorney, Austin had come by the trap house where Garcia hung out to pick up Garcia’s cousin; the cousin was in on the crime and had borrowed a box of gloves that Garcia frequently used, which is why Garcia’s DNA was found on the gloves at the crime scene; the reason Garcia’s cellphone pinged towers near Monte Sereno was because his cousin had borrowed it that night. However, the cousin died within weeks of the crime, and therefore wasn’t questioned or investigated.

The entrance of Raveesh Kumra’s residence, in Monte Sereno, California, a Silicon Valley enclave. CARLOS CHAVARRÍA/THE MARSHALL PROJECT

Jurors were not persuaded and convicted Garcia, along with Drummer and Austin, of murder, robbery of an inhabited place, and false imprisonment.

“I get it,” says Garcia’s attorney Christopher Givens. “People hear DNA and say, oh, sure you loaned your phone to someone.”

A jury could have had the same reaction to Anderson, had his alibi not been discovered, Givens says. “The sad thing is, I wouldn’t be surprised if he actually pleaded to something. They probably would have offered him a deal, and he would have been scared enough to take it.”

Garcia received a sentence of 37 years to life; Drummer and Austin’s sentences were enhanced for gang affiliation to life without parole. Garcia and Austin have appeals pending. Fritz received a reduced sentence for her testimony. In 2017 she was released from jail after spending four years in custody.

Lunsford received accolades for his detective work in the Kumra case and has since been promoted to sergeant; his boss, D’Antonio, is now a captain. But Lunsford says his perspective on DNA has forever changed. “We shook hands, and I transferred on you, you transferred on me. It happens. It’s just biological,” he says.

Based on interviews with prosecutors, defense lawyers and DNA experts, Anderson’s case is the clearest known case of DNA transference implicating an innocent man. It’s impossible to say how often this kind of thing happens, but law enforcement officials argue that it is well outside the norm. “There is no piece of evidence or science which is absolutely perfect, but DNA is the closest we have,” says District Attorney Rosen. “Mr. Anderson was a very unusual situation. We haven’t come across it again.”

Van Oorschot, the forensic science researcher whose 1997 paper revolutionized the field, cautions against disbelieving too much in the power of touch DNA to solve crimes. “I think it’s made a huge impact in a positive way,” he says. “But no one should ever rely solely on DNA evidence to judge what’s going on.”

Anderson’s case has altered the criminal justice system in a small but important way, says Kulick.

“As defense attorneys, we used to get laughed out of the courtroom if in closing arguments we argued transfer,” she says. “That was hocus-pocus. That was made up fiction. But Lukis showed us that it’s real.”

The cost of that demonstration was almost half a year of Anderson’s life.

Being accused of murder was “gut-wrenching,” he says. It pains him that he questioned his own innocence, even though, he says, “deep down I knew I didn’t do it.”

After he was released, Anderson returned to the streets. As is typical in cases where people are wrongly implicated in a crime, he received no compensation for his time in jail. He has continued to struggle with alcohol but has stayed out of major legal trouble since. He’s applying for Social Security, which could help him finally secure housing.

Anderson feels certain he’s not the only innocent person to be locked up because of transfer. He considers himself blessed by God to be free. And he has advice about DNA evidence: “There’s more that’s gotta be looked at than just the DNA,” he says. “You’ve got to dig deeper a little more. Re-analyze. Do everything all over again … before you say ‘this is what it is.’ Because it may not necessarily be so.”